‘Shashank Redemption’ at 30: Hope is a good thing

In October 1994, multiple star-studded films clashed at the box office. Starring Tom Hanks Forrest Gump Quentin Tarantino-directed and box-office hit Pulp Fiction Also his long awaited debut.

Also on offer for the fall movie was the Morgan Freeman-Tim Robbins vehicle Shashank RedemptionDirected by Frank Darabont. Based on the novel by Stephen King Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption (whose plot it follows quite faithfully), it was pitched as an inspirational jailbreak film; It offered the uplifting missive as its tagline: “Fear can hold you captive but hope can set you free.”

Unlike its peers though, this movie proved to be a box-office bomb. Despite being nominated for seven Academy Awards, its Oscar campaign yielded no results. But now, 30 years later, it has achieved cult-favorite status. Events were planned for the film’s anniversary this year, including a tour through the film’s filming locations in August, primarily in Ohio. The line ‘live a busy life’ or have a busy day’ has permeated the popular consciousness without any stamp of its origin. Its longevity has been attributed to cable television and home-video rentals—it became the most-rented film of 1995. Gradually, it gained credibility through word of mouth and is now considered a classic. And it’s widely ranked in the 90s and best movies of all time lists. Even today, it occupies the top spot of IMDb’s top 250 and top 100 films, indicating popular acclaim.

On the 30th anniversary of the movie’s release, we took a fresh look at it, as an avid filmhound might have on a night in October 1994.

Entering Shashank

The opening itself sets the tone of the movie: it’s grim, a little hopeless. Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) is parked outside the house of his wife’s lover. As it intercuts with the courtroom scene that condemns Andy to two life sentences for the murders of his wife and her lover, the audience is left in doubt as to what happened that night.

But no matter. In 1947, Andy arrives at the fictional Shawshank State Penitentiary. And here Alice ‘Red’ Redding (Morgan Freeman) is again being denied parole, as she has been for the past 20 years. As Red Muse, Andy doesn’t quite fit in with the rest of the prison crowd. It’s not his assertion of innocence that sets him apart—”don’t you know, we’re all innocent here,” his fellow prisoners tease—it’s something, almost carelessness, about his manner. Andy soon develops a camaraderie with Red, after approaching him for a rock hammer—a canon event in the film and the ultimate architect of his escape.

Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman sit outside on a bench playing checkers and talking about a scene from the film. Photo Credit: Archive Photo

The budding friendship at the heart of the film is woven with the disturbing dystopia of prison life. Some of the evils of the prison are revealed: a worm in Andy’s first meal, an inmate beaten to death by guards on his first night, repeated sexual assaults by Boggs and his crew. Others are more insidious, hinting at evil continuing without respite—evil through cut scenes, whispers, and vague dread.

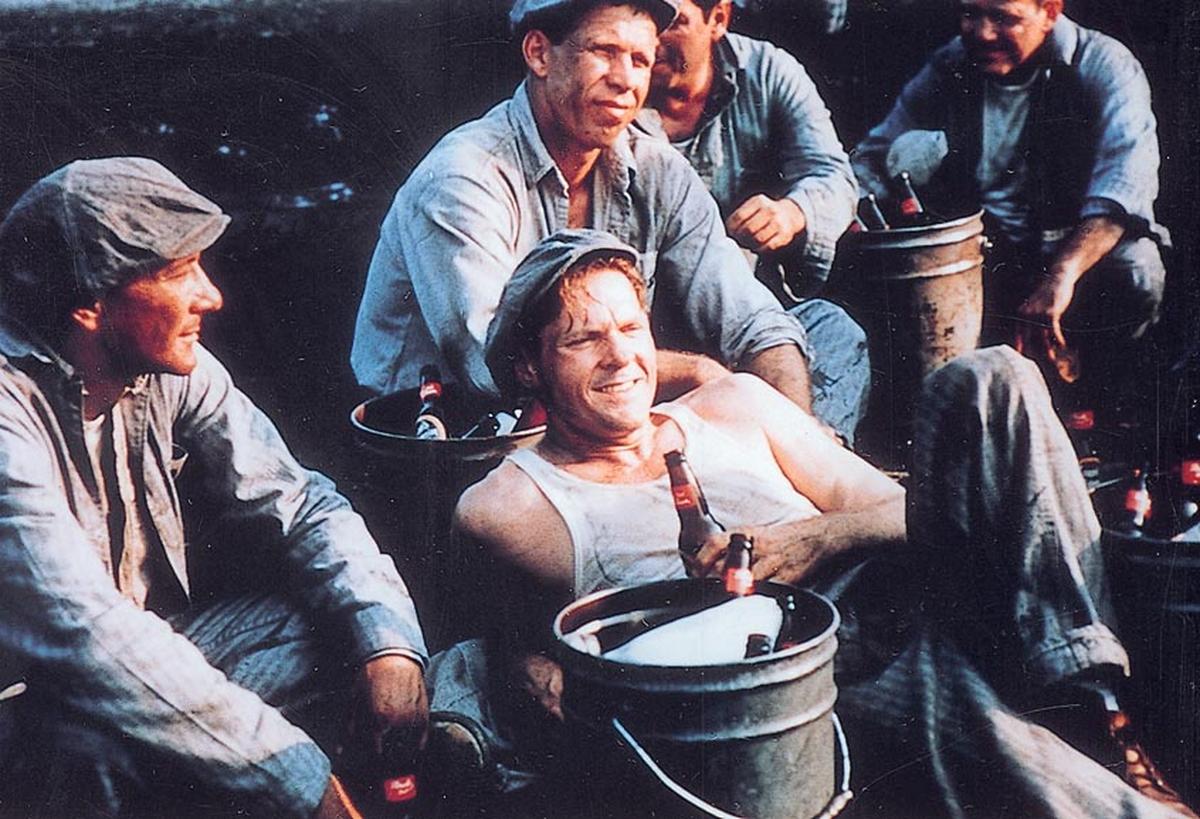

But the movie is not a prison documentary. It is a terrifying creation, but still remains a quasi-fantasy of life. If it is a newspaper article, perhaps, we will not get a remedy. But in Shashank RedemptionThere are moments of leisure. There is a library, which becomes big and beautiful. There is friendship, furthered by cold beer, Rita Hayworth and a little hope of music within.

Andy Dufresne is a harbinger of hope, and his Zihuatanejo may also be a stand-in for heaven. It fits; He is, after all, the underdog hero. Smart banker who took the fall for a crime he didn’t commit. The inspirational prisoner who doesn’t sink into the quicksand of fear but builds a library, helps people get an education, and gets into the warden’s good books. And finally, he escapes. He fits the hero archetype in every way.

But Red, cleverly played by Morgan Freeman, could be any guy. He is too strong to take over the friend archetype. He is the omniscient narrator, perhaps: the knowledgeable expert on each place, the one watching from the edge of the wall, too hard to relent or escape. He doesn’t want any trouble. He is faithful, but not faithful enough to be a member of society again. Indeed, when he declares his inability to be a part of society in any way, society allows him to rejoin.

release

As we realize, Andy has nothing to seek redemption, but the film offers him redemption for his non-sin. It also offers redemption for the audience, liberating the world for them as it liberates men from prison. It seems to study the beginnings of humanity after humanity leaves it up to you. Criminal or irregular, these are people lost to society, perhaps forever. What can survive in this empty environment? The story follows which many of the soft underbelly products of civilization don’t want to follow too closely.

A famous shot from the film

At least in the movie we never find out what Red did. He killed someone, yes, but who? for what The movie makes it irrelevant. His inhuman behavior does not completely strip him of his humanity. This is an advantage not afforded to Tommy, a hardened criminal now ready to try a life beyond his crime. He even brings hope to Andy, in the form of innocent evidence of the crime he was imprisoned for. But not all hope is allowed to flourish in Shashanka.

A still from ‘The Shawshank Redemption’

Another vexing question is: Who is to be declared a fit member of society? And further, what is acceptable to society — a pious man or a good person, a person in the trappings of honor or a soul with integrity? Who is allowed to be a person and not just a number on the prison register? The film challenges the notion that crossing the thin social line that separates average people in prison and on the street is reserved for a select few. We feel this sense of exclusivity among the prison guards, as if evil cannot be done by them or by them, and the warden, whose personal distance from the dirty work of engineering makes him feel safe. They create evil and power in a cursed dance, writs that ensure no one can touch them — or so they believe.

One of the film’s greatest tragedies is how a man becomes a creature of habit, even in a cruel, inhumane place. As inmates withdraw from society, some begin to prefer the certain horrors of prison to the uncertain horrors of the outside world. They are now institutionalized men, accustomed to the routines, structures, hierarchies, even of prison life. The outside world is chaotic, and they enter it as dregs of society, not as a Man Friday, as in Red Prison, or a well-liked prison librarian, as in Brooks Hulten before parole.

But the film’s most compelling claim, perhaps, is that all individuals are allowed to live a life—a flawed, wobbly, shaky little life. Time is wasted in prison, but life is still a bright truth worth preserving. Is this kinder than real life? After all, in real life, there is no guarantee of feeling the release of sun on your face, wind in your hair and green things growing around you. But God is beautiful. “Hope is a good thing, perhaps the best thing. And no good thing ever dies,” says Andy. And, almost fearfully, we believe him.

In light of the clarification 30 years later, it is surprising that the film did not do well in theaters. It doesn’t really feel like the kind of movie you watch for an afternoon and then go on with life as usual. It’s also not surprising that it’s one of the highest-grossing films of all time. You think about it, what it has given you, recommend it to whomever you want to do well, like a passed down wisdom. This has been happening for three decades. And every year, new visitors will find it, like a hopeful letter under a black rock that has no business under an oak tree in Texas.

has been published – October 18, 2024 04:43 pm IST